What are Dissociative Disorders?

Formerly known as Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD), pathological dissociation or Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) is a post-traumatic defence mobilized by the patient as protection from overwhelming pain and trauma. Dissociative symptoms occur within a variety of psychiatric diagnoses including personality disorders (such as Borderline Personality Disorder), post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), eating disorders, anxiety disorders, depression and schizophrenia. Dissociation is a condition that can be frightening to live with, can cause apprehension, confusion and disbelief among professionals and can be exhausting and despairing for carers, partners and relatives.

Research into dissociative disorders has a documented history going back some 350 years to the time of Mesmer. Here is a chronological table to show significant stepping stones on the pathway to its understanding and treatment. DissociationChronological table.

The case of Miss Beauchamp reported by Morton Prince (1908)

Prince’s study of the case of ‘Miss Beauchamp’ reported four alternating personalities. Prince was particularly interested in the inclusivity aspect of co-consciousness that was demonstrated by the Miss Beauchamp case, and he coined the term ‘co-conscious’ in order to avoid confusion:

Thus a ‘doubling’ of consciousness results of a personal self and the subconscious ideas. I prefer myself the term co-conscious to sub-conscious, partly to express the notion of co-activity of a second co-consciousness, partly to avoid the ambiguity of the conventional term due to its many meanings, and partly because such ideas are not necessarily sub-conscious at all; that is, there may be no lack of awareness of them (ibid, pp. 67-68).

Prince pointed out that all conscious states, ‘belong to, take part in, or help to make up a self’ (ibid, p. 76). He added that it is difficult to conceive of a conscious state that is not associated with a self-conscious self. Prince stated that it would seem ‘queer’ to think of a state of consciousness or sensation or perception, or idea, as ‘off by itself’ and not attached to anything we call the self. By emphasising the psychological, Prince insisted that he was not dismissing the physiological, and held that all thought is correlated with physiological activities. He believed that all mental phenomena would require both a psychological and a physiological explanation (ibid, p.68).

Although Prince was in agreement with Myers’ concepts of secondary selves (Myers, 1903), together with a psychological explanation in addition to a physiological one, it is difficult to reconcile his notion that all secondary centres of consciousness are to be considered a part of the self.

Prince’s report made no claim that outside intelligences were responsible for any of the alternating personalities, and yet personality number 3, ‘Sally’, insisted that she was not of Miss Beauchamp. Sally reported that she remembered Miss Beauchamp as a very small child learning to walk and talk. This implied that Sally had been with Miss Beauchamp from a very early age, but Sally herself was not of such a young age.

The inconsistencies of the Miss Beauchamp case prompt the question, was Sally a discarnate conscious spirit that was attached to Beauchamp and not a dissociated alter-ego as Prince assumed?

References

Myers, F. (1903). Human Personality and Its Survival of Bodily Death (2 Vols). New York, Longmans, Green & Co.

Prince, M. (1908). The Dissociation of a Personality: A Biographical Study in Abnormal Psychology. 2nd Ed. New York, Greenwood Press.

Mysticism and Religious Experience

A Dissertation for the degree of Master of Arts

Mystical & Clinical Perspectives of Dissociation

Department of Religious Studies

University of Kent at Canterbury

© 2006 Terence J. Palmer.

palmert55@gmail.com

Dissociation. Mystical and Clinical Perspectives.

Summary

In this dissertation it is hypothesised that negative mystical experiences and some mental illnesses are connected, and that the unitary factor that links all negative mystical experiences with dissociative disorders and other mental illnesses is fear. We begin with a brief glimpse at the intense fear experienced from a negative mystical experience. Further exploration examines the state of mind known as dissociation that facilitates mystical experience and pathology from the discoveries and theories of early researchers including Pierre Janet, Frederic Myers and William James, together with more recent research into the nature of altered states of consciousness and in consciousness itself. This dissertation further gives reference to qualitative phenomenological research that has discovered a direct relationship between Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) formerly known a Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD) and spirit possession. It is concluded that the radical empiricism and pragmatism proposed by William James more than a hundred years ago do offer a new epistemology for research into the nature of human consciousness. Quantum theory provides modern research into human consciousness and various psi phenomena with the conceptual framework to explain the evidence that supports earlier theories that minds other than our own can affect our thinking and behaviour.

For a complete pdf of the dissertation click on this link:

The following article is taken from the text of Chapter Thirteen of The Science of Spirit Possession 2nd edition (2014, p.265-270)

The Continuum of Mental and Emotional Disorders

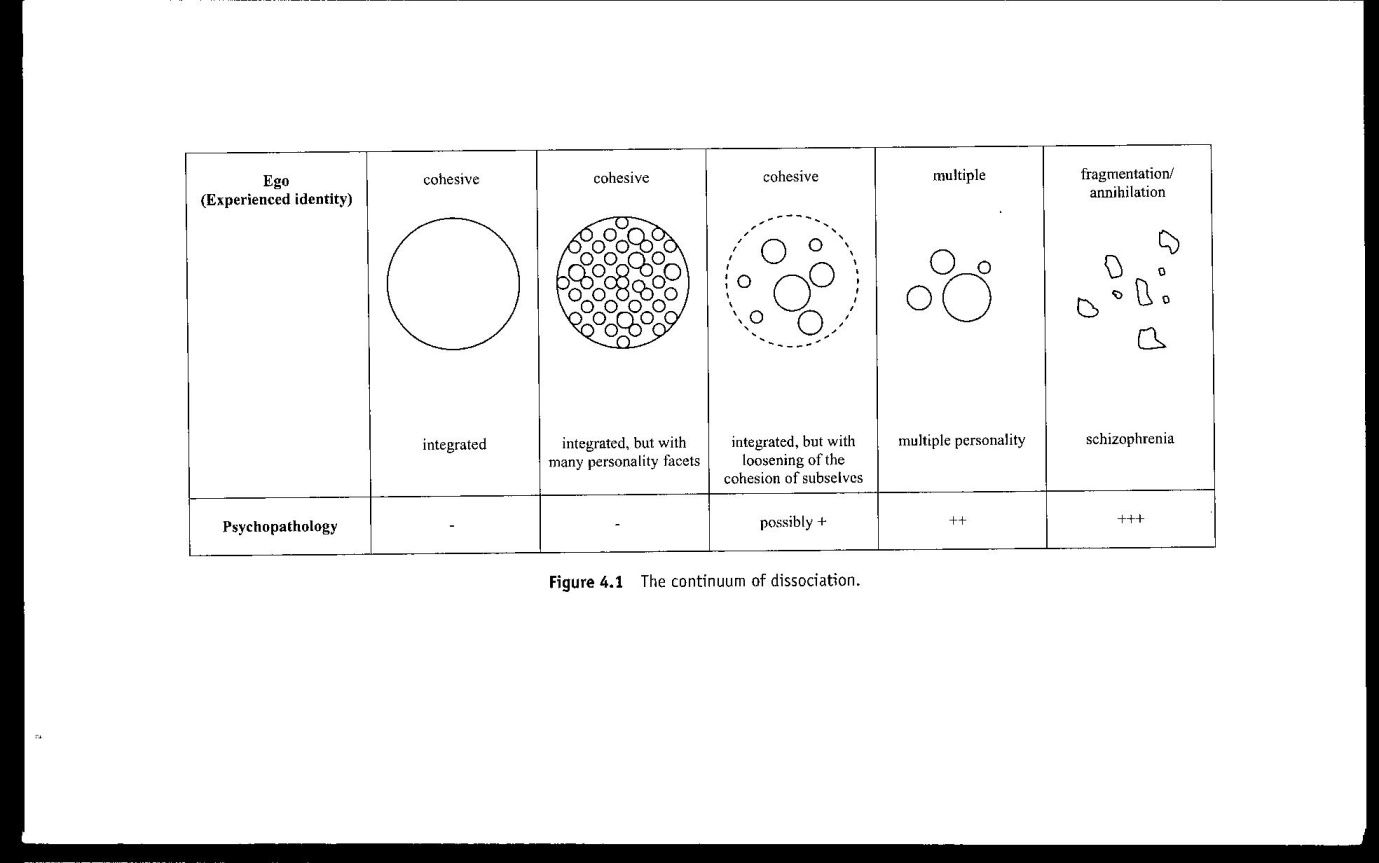

On the continuum of mental and emotional disorders, anxiety and depression may be seen to represent the thin end of the wedge, progressing in seriousness and intensity through the neuroses to borderline personality disorder, then to DID and ultimately to schizophrenia at the extreme end of the scale. The progression along this scale can be illustrated by a scale of ego-fragmentation conceived by Scharfetter (2009).

Scharfetter’s model enables us to identify how a progressively fragmented personality lends itself to an increasing potential for spirit influence. Scharfetter’s “ego” refers to the “experienced identity” of the 100% healthy individual who enjoys a cohesive, integrated personality. Moving one step along the scale we find a cohesive, integrated personality that is comprised of many personality facets. Each of these facets represents an ego-part that has the potential to emerge according to circumstances in the immediate environment that are similar to those that prevailed at the time the ego-part responded to external stimuli. Neurotics and the majority of so-called “normal” people would fall into this category. Moving along the continuum to the centre represents a loosening of the cohesiveness of the sub-selves and the boundaries with the external environment and would include borderlines. The next step along the continuum describes a dismantled boundary between the fragmented self and the environment, thereby constituting dissociative identities. The fifth and final stage along the continuum denotes a complete fragmentation of the self with no boundary with the environment, such as schizophrenia (Scharfetter, 2009, p. 56).

It is my contention that the one significant factor that unites these categories on the continuum is emotion. In Chapter Ten I explored the concept of sympathetic resonance as the predominant factor that attracts spirit entities (positive and negative) to a person who is transmitting a powerful emotional energy. Scharfetter’s model can be used to illustrate the progressive outcome of an inability to control powerful destructive emotions such as fear, anger and rage, etcetera. It is my contention that Fear, and the inability to deal with it in an appropriate way, is the primary cause of all non-organic mental illness and a highly significant factor in the attraction of negative spirit entities.

Adding support to the concept of the continuum, Richard Bentall challenges the proposition of Emil Kraepelin (1857-1926) who is the original architect of the modern psychiatry diagnostic system, that there are a number of discrete psychiatric disorders, each one associated with a distinct type of brain pathology (Bentall, 2004, p. 13). Bentall explains how the Kraepelinian model, which has evolved into the modern principle of arriving at a diagnosis based on the identification of presenting symptoms, has been maintained by mainstream psychiatric services. He argues that the maintenance of the diagnostic system based on symptomology is misleading and has no scientific foundation, and the thrust of his argument is extremely well supported by empirical evidence from a diverse array of anthropological, social, psychological and biomedical research (Bentall, 2004. p.13).

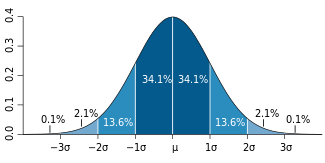

Bentall refers to research conducted at the Department of Experimental Psychology at Oxford University, where Gordon Claridge recognised an apparent continuum (the schizotypal scale) from sanity to insanity that necessitates a revision of the Kraepelinian model of psychosis (Bentall et al., 1989; 1990; Claridge, 2001). Claridge suggests that there is a normal distribution of the predisposition to develop psychosis, and that this predisposition can be triggered by environmental events such as psychological or physical traumas that could precipitate a psychotic breakdown (Claridge, 1990).

In parallel with Claridge’s schizotypal scale, Thalbourne (2010b) posits the concept of transliminality and sensory sensitivity. In Chapter Four, where I examined the methods of modern researchers in beliefs in the paranormal, I noted Thalbourne’s suggestion that transliminality may be a common factor in contributing to beliefs in the paranormal. Tranliminality can be seen as a predisposition to dissociate or enter into trance states or altered states of consciousness on a progressive scale.

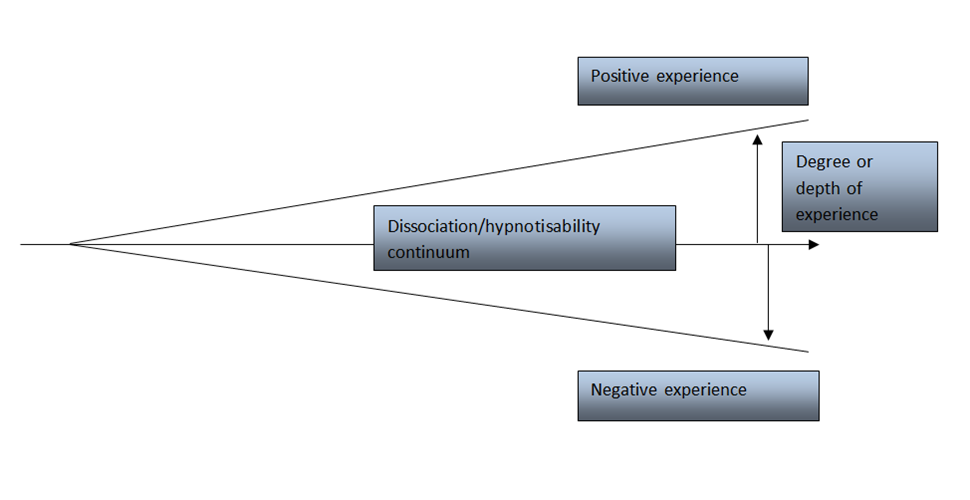

Elsewhere, Heap and colleagues have collected a total of 13 different hypnotisability scales (2004, p. 35). These scales differ in the number of qualitative criteria used, and consequently produce differing results. The two scales most often used in laboratory research are the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale (SHSS) and the Harvard Group Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility (HGSHS) (ibid, p.35). Extrapolating results from the collection of scales in order to arrive at a consensus of hypnotisability is extremely difficult, probably because hypnosis theorists are still unable to accurately define what hypnosis is. Nonetheless, it may be suggested that across the general population the ability to enter into a trance is evenly distributed with about 20% of the population having the ability to enter into a deep somnambulistic state. This simple diagram below may be used to illustrate these concepts.

On the continuum of trance experience, daydreaming represents the thin end of the wedge progressing through absorption (ibid, p.173) to dissociative states, to complete dissociation with a full out-of-body experience (Moody, 1975; Fontana, 2005) or soul-loss (Villoldo, 2005). It may be hypothesised that there is a correspondence between Claridge’s schizotypal scale, Thalbourne’s transliminality scale and Heap’s fuzzy and inconclusive hypnotisability. Any of these measures could hypothetically be used to identify vulnerability (the negative) or the potential ability (the positive) to spirit influence or possession.

Figure 13-1 The Trance Continuum

A predisposition to positive or negative possession could be translated into the language of ego strength and integrity (integrated, cohesive) using Scharfetter’s model or Claridge’s schizotypal scale, together with the ability to enter an altered state of consciousness. A correlation between decreasing ego-state integrity with an increase in predisposition to enter trance would indicate vulnerability. Conversely an increase in ego-strength (a strong sense of self) with a decrease in hypnotisability would indicate an innate and non-conscious resistance to spirit influence. Naegeli-Osjord suggests that possession vulnerability is somewhat dependent on a combination of weakness of the ego and high suggestibility (1988, p. 37).

Putting it simply, a person with a strong sense of self (ego-strength) with a high propensity to enter an altered state (to dissociate) will have the psychological means to protect himself and control any influence from an external source, depending on their knowledge and experience. Examples of this type of personality are those who invite positive possession, such as Mercy Magbagbiola who invited the Holy Spirit, Alberto Villoldo who undertakes shamanic journeying, and mediums who permit themselves to be used as instruments of communication for deceased relatives or other beings in the spirit realm (Morse, 2012). Conversely those persons with a fragmented personality or a very weak sense of self, and who have a high propensity to enter an altered state or to dissociate, will not have the means to protect themselves and exercise control over spirits that are attracted to them. Unfortunately none of these concepts are taken seriously by mainstream psychiatry, and any behavioural symptoms that signify spontaneous entry into trance states or complaints of spirit possession are automatically deemed to be pathological.

On a scale of 0 – 100, if you are one of those people at the 0-20 end of the continuum then you will not be influenced by suggestion or be aware of anything of a discarnate spiritual nature. You will not have mystical experiences and due to your analytical mind you will be rational in your explanations as to why others do have such experiences. You may also attribute your flashes of creative inspiration to your own subconscious rather than to any spirit guidance. However, as we move along the continuum then things do change. We become progressively more vulnerable and more susceptible to the power of suggestion, to creative or magical thinking, and to mystical experiences and spirit influence, and we may experience unexplained synchronicities. As we approach 80-100 at the extreme end of the continuum, those with a robust sense of self will be mediumistic and able to control the influence on them from the spirit world. These people will be spiritualist mediums or shaman. But those with a fragmented sense of self, or ego-fragmentation according to Scharfetter’s model, will be subject to psychosis and negative spirit possession.

Where the French psychiatrist Pierre Janet focussed on the negative, by his assertion that all those who experienced dissociation and psychic phenomena are mentally ill, Myers did not discount the positive and arrived at his tertium-quid approach and the continuum of human experience.

This is where the art and skill of the psychiatrist is tested. It is not sufficient to simply diagnose personality disorders, dissociative identity disorder (DID) psychosis or schizophrenia, but to consider the very high probability that the cause is spiritual in nature, especially when the symptoms are accompanied by auditory voice intrusions or command hallucinations. It is here that we are able to distinguish the difference between a healthy minded spiritualist medium (the positive) and someone who is psychotic (the negative). In contrast, someone at the lower end of the scale, like a scientist or a psychiatrist with an analytical and rational mind, will be influenced by their own abilities and experience and will not be able to appreciate the experience of the medium or the psychotic. This is where the value of personal experience comes into the art of discernment and in the scientific validity of unusual phenomena.

All human experiences exist on a continuum that can be illustrated with the normal distribution curve as shown below:

Figure 13-2 Normal Distribution Curve

Let us assume that at the extreme left of the curve are those who never experience spirit communication and at the other are those who do. In the middle are the majority of people within the population who do have some experiences of variable intensity and meaning. The normal distribution curve, or the 0-100 scale described above, can be used as simple models to illustrate the evolution of the expansion of human consciousness. At the 0-20 end of the spectrum and the extreme left of the distribution curve we may position mechanistic science, Newtonian physics and rational atheism. At the 80-100 end of the spectrum and the extreme right of the distribution curve we may place the transcendent, or alternate reality, or a pluralistic universe. In the centre we may place the advancement of physics into the domain of quantum theory and those mystical or religious experiences that prompt us to ask questions and seek explanations. This is my own simple logic and rational deduction to explain the movement of human consciousness towards a more holistic and balanced approach between science and spirituality for a greater understanding of so-called “anomalous” phenomena. As we progress in our evolution of scientific enquiry, so too does our consciousness expand so that we can accommodate such experiences into an expanded natural scientific framework.

Medical Diagnoses and Spirit Possession

Although “possession and trance disorders” are listed in the ICD-10 (World Health Organisation, 1992, p. 347) they are generally regarded as phenomena that are experienced primarily in tribal communities where shamanic practices are endorsed by the society, unless they are destructive in which case they are seen as pathological according to Western medical theories.

|

ICD-10 dissociative (conversion) disorders |

DSM-IV dissociative disorders |

| Dissociative amnesia | Dissociative amnesia |

| Dissociative fugue | Dissociative fugue |

| Dissociative motor disorders | Dissociative identity disorder |

| Dissociative convulsions | Depersonalization disorder |

| Dissociative anaesthesia and sensory loss | Dissociative disorder not otherwise specified |

| Dissociative stupor | |

| Possession and trance disorders | |

| Mixed dissociative (conversion) disorders | |

| Other dissociative (conversion) disorders | |

| Dissociative (conversion) disorder, unspecified |

Table 13-3 Dissociative disorder classes in ICD-10 and DSM-IV

In the above table “possession and trance disorders” are shown in relation to similar dissociative diagnoses in ICD-10 and DSM-IV. This table of dissociative disorders gives the impression of a series of discrete mental diagnoses that are related to each other by the term “dissociation”. The study of dissociative disorders has become hugely fashionable in recent years, particularly in the USA and Europe, with many dedicated clinicians and researchers attending much time and resources to its treatment and study, as the following references will testify; (Bernstein and Putnam, 1986; Cardena, 1992, 1994; Cardena et al., 2009; Corstens et al., 2009; Blizard, 1997; Dell, 2002; Dell and O’Neil, 2009; Dorahy and Green, 2009). A thorough review of all this literature on dissociation reveals that no one is considering the possibility that dissociation is connected with genuine spirit possession despite the fact that Possession and Trance Disorders is listed in ICD-10 (World Health Organisation, 1992) as shown in the table above. An example of the methodological atheism perspective of dissociation theorists is given below.

In their preamble to their chapter on possession and trance phenomena in (Dell & O’Neil, 2009) we are reminded by Cardena et al that the experience of “being taken over” has at various times been attributable to a variety of influences including “being inspired, or to the id, the Muses, Platonic manias, unconscious forces, Apollo or other gods, Jungian complexes, right hemisphere processes, or various types of spiritual forces” (2009, p. 171) and we are informed that research conducted by Bourguignon found that in a review of 488 societies 74% of people believed that spiritual forces can affect the personality, and 52% maintained that one’s own personality can be “replaced by that of another” (Bourguignon, 1973, p. 31).

Cardena and colleagues go on to cite Marjolein van Duijl, regarding her case of a 33 year-old patient in Uganda who experienced an alternate personality by regular attacks exhibiting aggressive behaviour and animal-like noises whenever her family made preparation to go to church. The clinicians suspected that the behaviours were in response to preparation to go to church or to pray because of her suppressed anger towards her father who was a strict and authoritarian Christian who ruined her life through his strict and unyielding principles, and therefore attributable to severe stress and serious inter-personal conflict. The client agreed to anger management counselling and medication to control her anxiety in anticipation of an attack. This case is cited because Cardena et al wish to emphasise the importance of differentiation between instances of possession that may benefit from medication, and possession experiences that are neutral or beneficial to the individual or the social community. Reading this case raises immediate serious concerns. The clinicians attribute the behaviour of the alternate personality to stress and repressed inter-personal conflict and prescribed the use of medication to subdue potential outward manifestation of aggressive behaviour. But what if their diagnosis was wrong? What if this woman was not suffering from repressed emotion due to stress and conflict? What if this woman was literally possessed by a spirit that finds church and prayer anathema? It would appear that the secular training of the clinician naturally assumes that real possession is out of the question and medication and anger management are the answer. But this was Uganda, and where was the shaman to give a differential diagnosis and solution more appropriate to the culture, or the church minister to affect deliverance from the offending spirit? Was the diagnosis the result of Western culture-bound preconceived ideas about the nature of spirit possession and an assumption that these kinds of experience are pathological?

In a case such as this, a spirit release practitioner would make no assumptions based upon preconceived ideas, but would engage the secondary personality through the client in hypnosis, or by direct contact through mediumship.

Possession/Trance Phenomena and Dissociation

In their structural definition of dissociative disorders Holmes et al (2005) have highlighted confusion with the meaning of the term dissociation in the literature and, following a brief review of conceptualizations, proposed that a distinction should be made between two separate processes: detachment and compartmentalization.

They define detachment as an altered state of consciousness characterized by a sense of separation from the self (depersonalization) or the world (derealisation). In addition, according to Holmes et al, some authors have suggested that it may have a distinct biological/physiological basis. They suggest that it appears to arise from intense fear, and in some circumstances it may develop into a chronic or recurrent condition, perhaps with environmental or intra-personal triggers. It is this relationship with fear that is of interest, and supports the trauma based theory of dissociation proposed by Janet (1976a).

They define detachment as an altered state of consciousness characterized by a sense of separation from the self (depersonalization) or the world (derealisation). In addition, according to Holmes et al, some authors have suggested that it may have a distinct biological/physiological basis. They suggest that it appears to arise from intense fear, and in some circumstances it may develop into a chronic or recurrent condition, perhaps with environmental or intra-personal triggers. It is this relationship with fear that is of interest, and supports the trauma based theory of dissociation proposed by Janet (1976a).

Compartmentalization, on the other hand, is characterized by an inability to deliberately control actions or cognitive processes that would normally be amenable to such control. In this phenomenon, the affected processes or information remain intact within the cognitive system despite being inaccessible; in this sense, they may be regarded as being compartmentalized. In this approach, detachment and compartmentalization differ in kind rather than degree, an approach that contrasts markedly with the traditional concept of the dissociative continuum. It is with these conceptual differences in mind that Holmes et al advocate different approaches in the clinical interventions related to the different forms of dissociation. So what would these different approaches be? How do you treat someone whose dissociation is detachment and how do you treat someone who is compartmentalised? Clues to the answers to these questions could be provided by the early hypotheses offered by James, Myers and Janet and with more contemporary spirit release practice.

Further to Holmes and colleagues’ categorisation, Cardena et al take experiential–detachment to mean an alteration in consciousness wherein “disconnection-disengagement from the self or the environment is experienced as out of body, depersonalisation, derealisation” (2009, p. 172). Psychological compartmentalisation according to Cardena et al refers to non-integrated psychological processes or systems that should normally be integrated, but can be subdivided into three categories of phenomena:

- Lack of awareness of current or previous information that should ordinarily be integrated.

- The coexistence of separate mental systems that should normally be integrated into consciousness, memoryor identity.

- On-going behaviour that contradicts introspective verbal reporting.

Possession Trance Phenomena (PTPs) according to Cardena et al mostly involve the first two categories; absence of reflective awareness (trance) and lack of integration of different identities (spirit possession). In an earlier paper Cardena (1994) declared that PTP phenomena have both pathological and non-pathological expressions and that in certain cultures, what could be seen as pathological in Western psychology, is in fact a socially acceptable phenomenon.

These conceptual differences between detachment and compartmentalisation could be compared with the two hypotheses presented between Myers and James on one hand (Myers, 1903) and Janet (1889) on the other. Dissociation by detachment could be due to the fissiparous nature of consciousness according to Myers and the shamanic tradition where soul parts are fractionated and escape from the psychic energy field of ordinary consciousness. Compartmentalisation fits with Janet’s theory where the dissociation is within the unconscious of the subject or, according to Myers and James, the influences of other entities that impinge on the subject (spirit possession). Should these conceptualisations actually fit with therapeutic practice then the therapeutic interventions would be entirely different for each type of case. In the case of detachment, should it actually mean soul loss then the lost soul parts need to be recovered and integrated into the whole person which is sympathetic with shamanic practice. In the case of subjective unconscious compartmentalisation the treatment would still be integration but with soul parts that are not lost. If the compartmentalisation is due to the influence of other entities then spirit release methods would need to be applied. However, due to the epistemology of modern scientific thinking the latter is not considered as a viable differential diagnosis by traditional medicine and psychotherapy.

It is my contention that all of the above dissociative-disorder diagnoses that are listed in ICD-10 and DSM-IV could be indications that spirit influence should be seriously considered as a differential or compound diagnosis. In cultural differences, according to Shweder (1985) “Possession is arguably the most common culture-bound psychiatric syndrome, and the experience of its converse “soul loss” perhaps more common internationally than depression” (cited in Littlewood 2009, p. 29). On this Littlewood writes:

Clinical presentation is most likely to be involuntary possession trance or the belief for which an individual presents as patient. They are commonly seen in clinical settings around the world, and in Britain are most likely to be seen among migrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh, the Middle East or North Africa (where the spirit is Jinn), and occasionally among evangelical Christians, though here the presentation is more likely to be possession belief alone (Littlewood, 2009, p. 31).

I pointed out earlier, in Chapter Two where I discussed beliefs in traditional religious rituals, that according to Littlewood, possession belief is an explanatory model that can be used to explain any illness, especially epilepsy and psychiatric disorder (2009, p. 34). Similarly, due to commonalities in phenomenology, possession states could be used to diagnose hysteria, multiple personality disorder or dissociative disorder. Traditional modes of dealing with spirit possession states normally include gently cajoling the spirit or accommodating it, rather than brutally expelling it, but the treatment practiced in Britain may be less confident and culturally validated. Littlewood therefore offers an alternative, by suggesting that in less developed cultures the possessing spirit may be gently cajoled or accommodated, but this is still seen as a socially accepted placebo from a Western medical perspective. In Chapter Four I introduced Hunter’s method of spirit release where he advocated use of the patient’s belief system (Hunter 2005, p.156) and this could also be seen as a form of placebo where beliefs and suggestion are the principle therapeutic factors. However, if we are to be able to discern whether a person is actually being influenced by an external entity that has ontological status, or whether they are responding to a belief, then we need to engage the entity in dialogue in order to determine its origin and objectives.

Dissociation and Paranoia

The debate about the confusion between multiple personality and possible spirit possession has its origins in the 19th century when Professor James Hyslop, professor of logic and ethics at Columbia University from 1889 to  1902, and editor of the American Journal of Psychical Research wrote:

1902, and editor of the American Journal of Psychical Research wrote:

The term obsession is employed by psychic researchers to denote the abnormal influence of spirits on the living…. The cures affected have required much time and patience, the use of psychotherapeutics of an unusual kind, and the employment of psychics to get into contact with the obsessing agents and thus to release the hold which such agents have, or to educate them to voluntary abandonment of their persecutions…. Every single case of dissociation and paranoia to which I have applied cross-reference has yielded to the method and proved the existence of foreign agencies complicated with the symptoms of mental or physical deterioration. It is high time to prosecute experiments on a large scale in a field that promises to have as much practical value as any application of the scalpel or the microscope (Wickland 1924:8-9).

The observation by Hyslop that “every single case of dissociation and paranoia … are complicated by the presence of foreign agencies” provides initial support for the hypothesis that dissociative disorders can be confused with spirit interference. Furthermore, Hyslop’s reference to “the use of psychotherapeutics of a very unusual kind, and the employment of psychics to get into contact with the possessing agents” is arguably the first mention of a treatment method that has subsequently become known as Spirit Release Therapy.

The treatment of Dissociative Identity Disorder with ‘Telepathic Hypnosis‘ is the subject of ongoing research. Please help take this research forward by becoming a patron. Many thousands of sufferers could benefit from your patronage and save our NHS millions in medication costs. Thank you.

Some useful titles on dissociation.